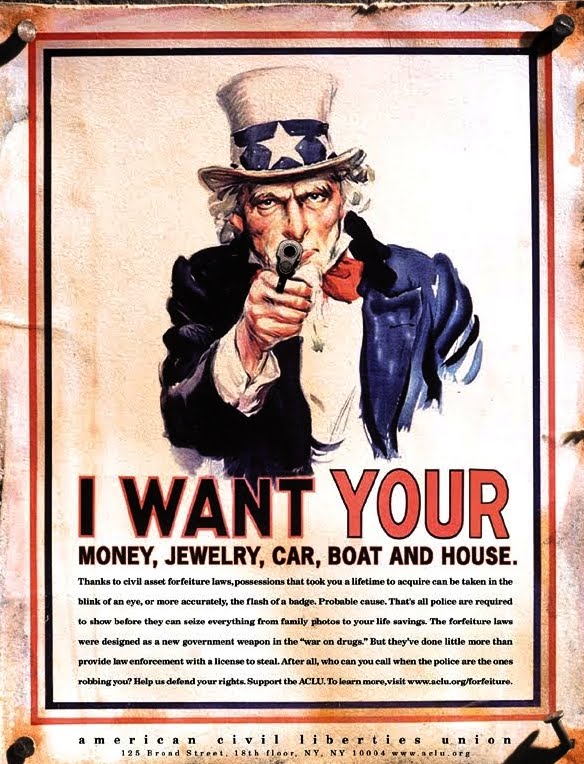

Courts currently interpret the Constitution to permit government seizure of assets from persons who have not been charged with a crime. How can this possibly be constitutional? How can a society so fundamentally based on the rule of law and individual due process permit the seizure of private property by highwaymen wearing law enforcement uniforms? Can civil property forfeiture in the United States in the 21st century be acceptable? At last, it appears, perhaps the Supreme Court will soon be ready to reconsider this whole subject matter. Justice Clarence Thomas suggested as much, armed with powerful statements casting real doubt on the constitutional validity of civil property forfeiture processes in the U.S.

Let’s outline this subject philosophically. We do so unencumbered by the long, winding, and arguably tortured history of civil forfeiture laws in the United States. We also do so without the use of labels that tend to color conclusions.

The Ownership of Private Property is Essential to Our Basic Notion of Liberty

We govern our approach with a basic concept involving natural law. We premise it on John Locke’s core view that:

Reason, which is that Law, teaches all Mankind, who would but consult it, that being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his Life, Health, Liberty, or Possessions.

Further to this fundamental view is the principle that private property is an essential part of human liberty:

Every Man has a Property in his own Person. This no Body has any Right to but himself. The Labour of his Body, and the Work of his Hands . . . are properly his. . . The great and chief end, therefore, of Mens uniting into Commonwealths, and putting themselves under Government, is the Preservation of their Property.”

We do not require a more detailed philosophical exploration of private property and natural law for our limited purposes.

The Bill of Rights Recognizes the Natural Law Property Principle

The Fifth Amendment provides that no person shall “be deprived of . . . property without due process of law. . . ” We do not explore Supreme Court analyses and applications of this Fifth Amendment principle as that, too, is beyond the scope of our purposes.

The Principles That Should Govern the Concept of Property Seizure

We suggest a core of ten basic principles that should govern the seizure of property under our Constitution. These principles fall into two basic sub-categories.

Principles Regarding Property

Five of these principles are precepts regarding the property itself, and the ownership and control of property in the United States.

1. Property in the possession of an individual is presumed to belong to that individual.

2. Property cannot be removed from an individual’s possession against his will, either by physical force or by mandatory compulsion.

3. Property does not perpetrate a crime. It cannot be guilty of a crime.

4. The human perpetrator of a crime may use property as an implement in the commission of a crime.

5. The government may deprive an individual of possession of property only as the consequence of a judicial process with due process rights.

Principles Regarding Persons and Crimes

The remaining five principles are precepts with direct applications to persons under our Constitution.

6. Persons commit crimes. Property does not commit crimes (the corollary to precept number 3, above).

7. We presume that individual persons protected by the Constitution are innocent of crimes.

8. Persons covered by the Constitution and charged with crimes have the right to a judicial due process to determine their guilt.

9. The burden of proving an individual’s criminal guilt is on the government. The government must demonstrate that guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

10. A person may be punished for a crime only after he is found guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Punitive action may include, among other things, the seizure of the property used by the guilty person in the commission of the crime.

Our Principles Work – Civil Property Forfeiture Proceedings Must Instead Become Criminal Proceedings

Our approach aligns forfeiture concepts with due process principles. Many forfeiture statutes that deny due process rights rely on historical anachronisms. These statutes and their related procedures deprive adversely impacted individuals of their property. Justice Thomas cited some of those anachronisms in his statement in Leonard v. Thomas, 580 U.S. ___ (2017).

As Justice Thomas points out, “modern civil forfeiture statutes are plainly designed, at least in part, to punish the owner of property used for criminal purposes.” In order to mete out such punishment, the government must respect the individual’s due process protections. Civil forfeiture statutes generally deny these protections under the fiction that forfeiture is a “civil” not criminal matter.

The Constitution, Freed From Historical Anachronism, Invalidates Forfeitures Without Due Process

The historical “justification” for denying individual’s due process rights with respect to seized property has been the essential fiction that government may “punish” the property itself. As Justice Thomas observed, courts have based this justification on “a discrete historical practice that existed at the time of the founding [of the Untied States].”

Indeed, this “historical practice” focused on allowing the government to “proceed in rem [against the property] under the fiction that the thing itself, rather than the owner, was guilty of the crime.” Our approach corrects for this legal fiction, which is the key foundation of the historical forfeiture record. Instead, we base our approach strictly on the notion that people, not property, commit crimes. We premise our approach on reality, not legal fiction. Property is not “guilty of the crime.” Individuals are.

Justice Thomas’ Constitutional Perspective

As Justice Thomas points out, “in the absence of this historical practice, the Constitution presumably would require the Court to align its distinct doctrine governing civil property forfeiture with its doctrines governing other forms of punitive state actions and property deprivation.” Justice Thomas went right at the heart of forfeiture matter, positing two constitutional defects in the current forfeiture approach:

First, historical forfeiture laws were narrower in most respects than modern ones. . . . [T]hey were limited to a few specific subject matters, such as customs and piracy. Proceeding in rem [against the property] in those cases was often justified by necessity, because the party responsible for the crime was frequently located overseas and thus beyond the personal jurisdiction of United States courts. . . . These laws were also narrower with respect to the type of property they encompassed. For example, they typically covered only the instrumentalities of the crime . . . not the derivative proceeds of the crime.

Thus, Justice Thomas suggested that many forfeiture laws are unconstitutionally broad for one of two reasons. First, to the extent that they may apply beyond situations where criminals are outside of the United States where the U.S. could only reach property existing inside the U.S. Second, to the extent that the property covered by the forfeiture is other than the property itself used to commit the crime.

Then, Justice Thomas noted, the courts’ historical rationale that permitted civil forfeitures was muddled at best:

Some of this Court’s early cases suggested that forfeiture actions were in the nature of criminal proceedings . . . . Whether forfeiture is characterized as civil or criminal carries important implications for a variety of procedural protections, including the right to a jury trial and the proper standard of proof. Indeed . . . there is some evidence that the government was historically required to prove its case beyond a reasonable doubt.

It’s Time to Harmonize Forfeiture Laws With Constitutional Principles

The chronicle of governmental civil property forfeiture abuse is long and inglorious. The impact of civil property forfeiture proceedings fall unfairly on the poor. Victims are typically those who cannot mount the necessary legal defense. The system in many states is abhorrent and unnecessary. In those states, it is unconstitutional too.